Building trust

COVID-19 forced us all to think differently about data

The COVID-19 pandemic has highlighted the world’s reliance on data, whether to fight the virus or for day-to-day transactions previously conducted in person that suddenly went online. Weddings, funerals, medical care, and grocery shopping have been reduced to a computer-intermediated experience on the Internet.

Countries with robust e-transactions laws have transitioned more easily to e-commerce and online public service delivery than countries forced to build technical and legal infrastructure from scratch. Not only have glitches tested people’s patience, but the new volume of internet traffic has also strained global communications infrastructure. And all that traffic is data.

The amount of data collected and processed—all kinds of data, personal and nonpersonal, actively provided or passively generated—has ballooned to unprecedented levels. The sheer volume of data has also raised awareness about their vulnerability to breaches, especially personal data.

Trust in data has been strained under emergency regulations

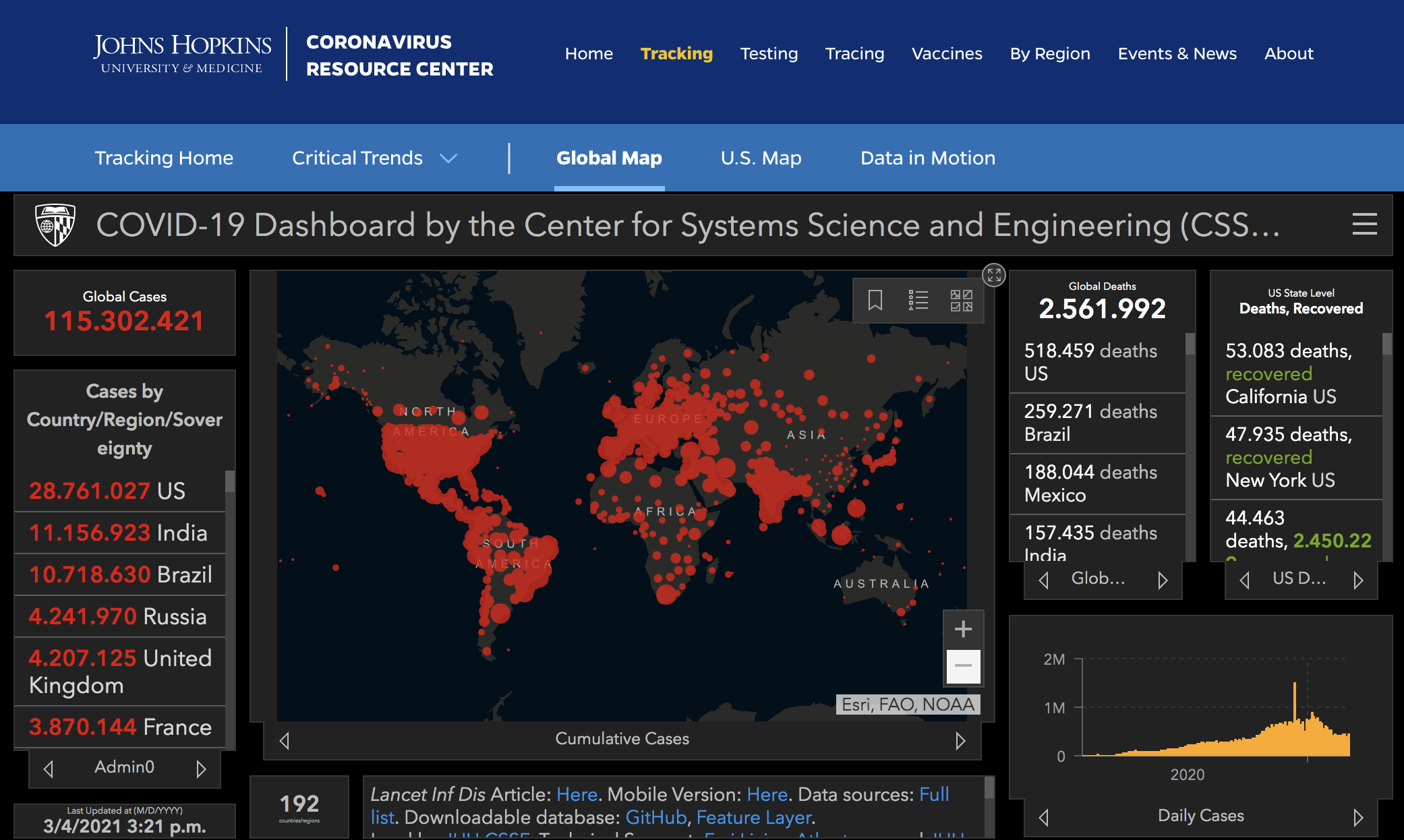

Much of the data generated and used to combat COVID-19 started as personal data. Personal data have sometimes been anonymized, and when combined with other private and public data, have resulted in new and powerful ways to understand trends, as shown in the COVID-19 Dashboard, operated by Johns Hopkins University. Health data collected during the pandemic have also been used to inform policy responses and better target resources for the delivery of social services.

Contact tracing

Digital contact tracing—something virtually unknown to most people until 2020— became a source of heated debate about how to collect and use personal data effectively while ensuring trust. Should contribution of data be mandatory? What protections would be afforded to the data collected? For what purposes would that data be used? And for how long should they be retained?

As contact tracing applications have spread globally to keep up with the virus, different countries have applied different approaches. The effectiveness of some of these apps—measured by how much they have been downloaded and used—is tied to the trust that citizenry have in the security of the systems and in how those systems would treat their data.

In order for the contact tracing effort to provide meaningful, actionable insights into how the virus move across borders, it became clear that the data collection platforms and systems and the way data were processed would need to work seamlessly (be interoperable). Despite efforts to promote such interoperability, including through the development of the operating system jointly designed by Apple and Google, and the European Union’s “toolbox” on common technical standards for its member countries, the applications developed by countries globally still differ enough to make the reality fall short of aspirations.

COVID-19 exposed weaknesses in global data standards

The early uses of data in response to the COVID-19 pandemic raised questions about how and by whom common standards should be developed, whether adopting interoperability standards should be mandatory, and whether national pandemic responses would even allow the development of common rules and standards for how data should be collected, managed, and exchanged across borders. These issues have reemerged with the development of vaccines, with differing standards for the collection of vaccine data and restrictions on the transfer of personal health data between certain jurisdictions. This has made it harder to compare vaccine efficacy data or pool them to do advanced analytics.

In seeking to increase access to data to address these novel circumstances, many governments adopted emergency legislation to permit the use of personal data; others suspended existing laws protecting personal data to allow their unfettered collection for purposes of combatting the pandemic. In some cases, these laws were adopted in a transparent way, were designed to be explicitly temporary, and included clear end dates to ensure a return to normalcy. Other laws did not include such safeguards critical to due process and government accountability.

Access to vaccines and the use of vaccine passports also raises broader concerns that go to the heart of the social contract around data. As with contact tracing, similar data protection concerns will apply to vaccine certificates. For example, is only the minimum amount of data being collected? Are data collected only for the limited purpose of linking a person to inoculation? How long will that data be valid? In addition, broader questions around equity—as well as the potential bias and discrimination that may result from the use of vaccine certificates, these tools, and their underlying data—must be addressed.

The Global Data Regulation Survey

To capture information on the robustness and completeness of normative frameworks for data governance around the world, this World Development Report conducted a Global Data Regulation Survey. It collects information on dozens of attributes of the regulatory framework in 80 countries (covering 80 percent of the world’s population) selected from different global regions and country income groups across the development spectrum.

The Survey is based on a detailed assessment of domestic laws, regulations, and administrative requirements reflecting the regulatory status of each country as of June 1, 2020. Survey results are summarized in a variety of subindexes that capture different aspects of the regulatory environment for safeguards and enablers.

Safeguarding the Use of Data

Across the 80 countries surveyed, about 40 percent of the elements of good-practice regulatory safeguards are in place. Although scores range considerably, from less than 35 percent in low-income countries to more than 50 percent in high-income countries, the results highlight that even among the latter the regulatory framework is far from complete.

Countries by safeguarding score

Source: World Development Report 2021, Data for Better Lives, Global Data Regulation Survey.

Safeguarding personal data

To better address underlying concerns about the power asymmetries between individuals (and increasingly, groups) and those who control or process data, this Report advocates a rights-based approach to the protection of personal data. These rights are both substantive (including the right to control how data are collected, used, disclosed to, or shared with third parties) and procedural (including ensuring that data are used in a transparent, proportionate, and accountable way, and that those who suffer a data breach are notified and can be compensated through meaningful redress mechanisms). These rights are usually paired with obligations imposed on parties that control the data being collected, processed, or used to ensure that these rights are respected.

The fundamental rights that individuals have regarding their data are protected to enable their agency and control over the data that they produce or through which they can be identified, so that these data are not misused, such as for targeting, surveillance, or discrimination.

Country scores for safeguarding personal data

Source: World Development Report 2021, Data for Better Lives, Global Data Regulation Survey.

The figure that follows shows the percentage of countries in each country income group that have adopted elements of a robust legal and regulatory framework to safeguard personal data (as of June 1, 2020). The figure highlights the key rights individuals have for their data, as well as the limits on the collection, processing, and use that third parties must comply with to promote trust in data use and respect the social contract around data.

Source: World Development Report 2021, Data for Better Lives, Global Data Regulation Survey.

Nearly 60 percent of countries surveyed for this Report have adopted such laws, ranging from 40 percent of low-income countries to almost 80 percent of high-income countries. Although many lower-middle-income countries have laws on the books, their enforcement is uneven: only 30 percent of low-income countries and 40 percent of lower-middle-income countries have created a data protection authority.

These exceptions are widespread in all surveyed countries that have data protection legislation. Most of these exceptions are limited and pertain to specific data uses, such as in relation to national security (as in Brazil and India) or in transactions involving health data (as in Gabon). Other countries have passed laws that provide for more wide-ranging exceptions, including exemption from the requirement to obtain consent from data holders when performing lawful government functions such as delivering public services.

More than one-third of high-income countries require justification for the exceptions, while less than 10 percent of surveyed low-income countries place such process limitations on government action. This lack of limitations creates additional opportunities for unchecked state surveillance or mission creep, thereby undermining trust in data use.

Protecting personal data relies on imposing limits on how data about individuals (data that could be used to identify them) are collected, processed, and used. Only 18 percent of countries surveyed have adopted provisions imposing robust limits on data collection and use that are critical to protecting personal data. Provisions on purpose limitation are found in 79 percent of high-income countries; 62 percent of upper-middle-income countries; 53 percent of lower-middle-income countries; and 40 percent of low-income countries.

Moreover, 18 percent of the legal frameworks for data protection in the countries surveyed include a requirement to protect data by design. Provisions to this effect are found in 36 percent of high-income countries; 14 percent of upper-middle-income countries; and 23 percent of lower-middle-income countries.

Only about 30 percent of countries surveyed have put in place measures to restrict decision making based on automatically processed personal data. Among these, Côte d'Ivoire has included provisions in its Data Protection Act that prohibit the use of automated processing of personal data in judicial decision making to prevent bias.

Cybersecurity and cybercrime

Trust can also be built by improving cybersecurity and curtailing cybercrime. The scope of cybercrime is typically understood to include unauthorized access to a computer system (sometimes called hacking), unauthorized monitoring, data alteration or deletion, system interference, theft of computer content, misuse of devices, and offences related to computer content and function

Cybersecurity encompasses the data protection requirements for the technical systems used by data processors and controllers, as well as the establishment of a national Computer Security Incident Response Team (CSIRT), an expert group that handles computer security incidents. In addition to dealing with the criminal behaviors discussed, cybersecurity also builds trust by addressing unintentional data breaches and disclosures (such as those resulting from badly configured servers) and holding firms accountable.

Source: World Development Report 2021, Data for Better Lives, Global Data Regulation Survey.

The figure that follows shows the percentage of countries in each country income group that have adopted robust policy, legal, and regulatory frameworks for cybersecurity and cybercrime (as of June 1, 2020).

Source: World Development Report 2021, Data for Better Lives, Global Data Regulation Survey.

Countries surveyed differ in terms of their adoption of cybercrime laws that criminalize the full scope of unauthorized activities. The results are correlated with income level. While around 70 percent of upper-middle-income countries have such cybercrime laws, only 60 percent of lower-middle income and less than half of low-income countries have adopted similar provisions.

CSIRTs are far more prevalent in countries than other elements of a robust framework for cybersecurity/cybercrime. Laws, regulations, or cybersecurity policies that provide for the creation of a national CSIRT/CERT (Computer Emergency Response Team) can be found in all high-income countries and in about one-third of low-income countries.

Overall, the Survey reveals a low level of uptake of cybersecurity measures. None of the low-income countries surveyed has legally imposed a full range of security measures on data processors and controllers. Even among high-income countries, barely 40 percent of those surveyed require data processors and controllers to comply with these security requirements.

Around one-third of countries, across all income groups, have policies or laws that specify security requirements for the automated processing of personal data. Among the lower-middle-income group, an example of good practice is the comprehensive cybersecurity requirements in Kenya’s new Data Protection Act.

Enabling the Use of Data

Across the 80 countries surveyed for this Report, just under half (47 percent) of the elements of a good-practice regulatory framework for enabling data use and reuse are in place. The scores range considerably, from 30 percent among low-income countries to 62 percent among high-income countries. Although Estonia and the United Kingdom stand out among the high-income countries surveyed as the most advanced enablers, their performance is matched in the middle-income group by Mexico. Several other low-income and middle-income nations are also making progress establishing regulatory frameworks to enable data reuse, such as China, Colombia, Indonesia, and Nigeria.

Country scores for enablers for trusted use, reuse, and sharing of data for development

Source: World Development Report 2021, Data for Better Lives, Global Data Regulation Survey.

Enabling the use of public intent data

The figure that follows focuses on enablers for public intent data: specifically, data that are generated or controlled (or both) by the public sector (otherwise known as public sector data). To date, governments have had more control over mandating access to public sector data than data produced by the private sector, barring exceptional cases.

Country scores for enabling the use of public data

Source: World Development Report 2021, Data for Better Lives, Global Data Regulation Survey.

For public sector data, governments can employ several policy and legal tools to directly mandate access to and sharing of data—indeed, some already do so for certain health, patent, and even airline passenger data. By contrast, most data transactions involving the private sector are based on voluntary contractual agreements. The government’s role is largely limited to creating incentives to promote private sector data sharing.

The figure that follows shows the percentage of countries in each country income group that have adopted elements of a robust legal and regulatory frameworks to enable access, use, and reuse of public intent data (as of June 1, 2020).

Source: World Development Report 2021, Data for Better Lives, Global Data Regulation Survey.

Open data laws are considered to be the most decisive approach governments can use to enhance access to public sector data and enable their reuse by third parties to create value. About one-third of surveyed countries have open data legislation. Such legislation is more common in high-income countries.

As countries’ open data systems mature, governments should move from merely promoting access to data to facilitating their use, by ensuring that data and metadata are “open by default” and prioritized for publication based on user needs, made accessible in an open and machine readable format, and made available via bulk download or application programming interfaces (APIs).

More than 70 percent of countries surveyed have adopted access to information legislation—cutting across all income groups. The effectiveness of this enabler for public sector data depends on how broadly exemption categories for disclosure are drafted or interpreted. This is a key limitation in practice. Nearly half of the countries surveyed—across the income spectrum—have placed significant exceptions on the right to access public sector information.

A key enabler of data reuse is a data classification policy that categorizes types of data according to objective criteria that are easy to implement across the different stages of the data life cycle. Although data classification policies are found in more than half the countries surveyed, their practical effects are limited because the application of data classification policies for government database or document management systems is mandatory in less than one-third of countries.

For the value of data—including open data—to be fully harnessed, legislation must go beyond promoting access to data and ensure that data can be used more effectively by combining or linking datasets. Doing so requires provisions governing the interoperability of data (and metadata) and their quality, as well as the modalities under which data should be published. Interoperability of data and systems can be supported by adopting harmonized standards—ideally, open standards.

To support their reuse, public intent data should also be published under an open license and at no charge or at a marginal price to cover the costs of dissemination or reproduction. Nearly 48 percent of the surveyed countries have adopted some form of open licensing regime for public intent data. All the high-income countries covered in the survey have done so, compared with about one-third of low-income and middle-income countries.

Enabling e-commerce

Many data uses or transfers are accomplished through electronic transactions. Individuals using their data to transact online need to know that these data are being used in a safe and secure manner. Laws governing e-commerce and e-transactions provide an overarching legal framework that helps create trust in both public and private sector online data transactions, which in turn encourages use of data online. So legislation on e-commerce is an important part of enabling legislation.

Country scores for enabling e-commerce

World Development Report 2021, Data for Better Lives, Global Data Regulation Survey.

The figure that follows shows the percentage of countries in each country income group that have adopted elements of a robust legal and regulatory frameworks to enable reliable and trusted e-transactions (as of June 1, 2020).

Source: World Development Report 2021, Data for Better Lives, Global Data Regulation Survey.

More than 70 of the countries surveyed, including about 60 percent of low-income countries, have such laws, with little variation across country income groups.

The e-commerce legislation in the majority of countries surveyed includes such provisions—an unsurprising finding given that model laws on e-commerce were promulgated in the late 1990s. For instance, provisions enabling e-transactions are found in Morocco’s Law № 53-05 (2007) and good-practice provisions are embedded in Thailand’s Electronic Transactions Act 2019 amendments.

Legal recognition of electronic signatures is the one area in which high-income countries remain far ahead of low-income and middle-income countries.

Although the use of digital identity verification and authentication tools is on the rise, less than half of surveyed countries have government-recognized digital identification systems that would enable people to remotely authenticate themselves to access e-government services; those that do are mainly higher-income nations.

The principle of technological neutrality has been implemented in e-commerce laws or regulations of 53 percent of low-income and 57 percent of upper-middle-income countries, in contrast to 71 percent in high-income countries and 80 percent in lower-middle-income countries.